AI Didn’t Just Kill Jobs — It Helped Me Reclaim My German Citizenship

Note: This article isn’t sponsored and I have no affiliation with any tool, company or organization mentioned. I’m sharing the tools and resources I personally used in my own research journey.

Today, AI is killing journalism. It’s devouring tech jobs. It’s flooding the internet with garbage. And yet, AI also helped me reclaim my family’s forgotten German citizenship.

Without AI tools, I would’ve struggled to read centuries-old handwriting, navigate the bureaucracy of the Bundesverwaltungsamt (yes, that’s a mouthful. I’ll call it the BVA for the rest of this article), and even draft the cover letter that anchored my case.

At a time when AI is so often cast as the villain, it can also be an unlikely hero — when it’s used to empower instead of erase.

An Unexpected Discovery

My family history journey started with simple curiosity on Ancestry.com, the way it does for many people.

I wasn’t expecting much, maybe some census records, a few blurry photos if I was really lucky. But what I discovered stopped me in my tracks: my mom’s side of the family came from Germany. Not “from Germany” in the vague sense of a German surname or a sliver of DNA on a pie chart, but in the very real sense that my mom’s great-grandfather had packed up his life, crossed an ocean, and started over in Louisville, Kentucky in the late 19th century.

When I asked my mom about it, she shrugged and said, “Yeah, seems like I remember something about that.”

At the time, I found it surprising that an entire migration story — an ocean crossing, a new life, a German family line changed forever — could simply be forgotten.

But the more I learned about why, the less surprising it became: the World Wars had created such intense anti-German sentiment in the U.S. that, in a single generation, much of the culture vanished.

But that moment with my mom stuck with me. It made me realize that family history isn’t always passed down in polished stories or cherished heirlooms. More often, it fades into silence, tucked away in church records and passenger manifests, waiting for someone generations later to come looking.

And that’s exactly what I did.

Tracing Roots, Hitting Walls

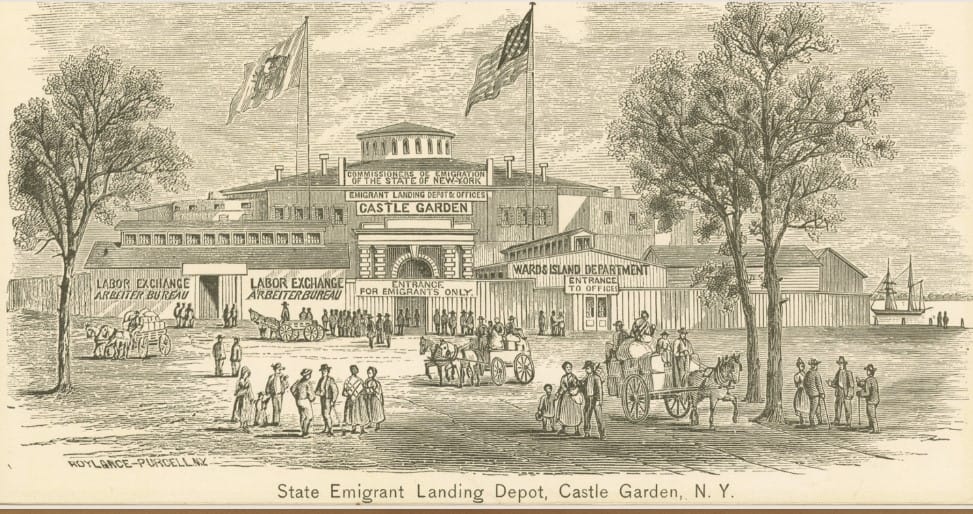

As I dug deeper into my family’s history, my great-great-grandfather Wilhelm became more than just a name on a passenger manifest or a line on an immigration list from Castle Garden (the predecessor to Ellis Island in New York). He was a man from a small village called Sapelloh in Germany, and with every new detail I uncovered, he felt less like a distant record and more like a real person.

But following those details back wasn’t easy.

Once I moved past census records and immigration lists, the trail leads into Germany — into old church books written in 19th-century handwriting styles known as Kurrent and later Sütterlin. These scripts were once taught in German schools but abandoned by the mid-20th century.

Today, reading Kurrent is a dying skill. When I sent a message to my local German heritage society about getting help reading it, they told me the last person in their group who could read the script had passed away, and no one was left who could read it.

Finding someone today who can is rare — and the further you go back, the harder it gets, as old German records often mix with Latin and the handwriting itself becomes increasingly difficult to decipher.

But handwriting wasn’t the only problem. Many of these records, if they survived world wars and fires, still sit locked away in parish archives or regional church basements, fragile and hard to access. They exist, but were out of reach for most family historians, until a project came along that started pulling those archives online.

Archion’s Digitization Project

Even if I could magically read every curl of Kurrent, most of the records I needed were in Germany. For someone sitting in the U.S., those books might as well have been on the moon.

That changed when I found Archion.

Archion is a massive digitization project run by the Protestant Church in Germany. Their mission is simple but ambitious: scan millions of church records and put them online. For researchers, it was nothing short of a lifeline. Suddenly, instead of booking a flight and begging for access to a parish basement in Lower Saxony, I could log in, pay a modest subscription, and scroll through the very same records from my desk at home.

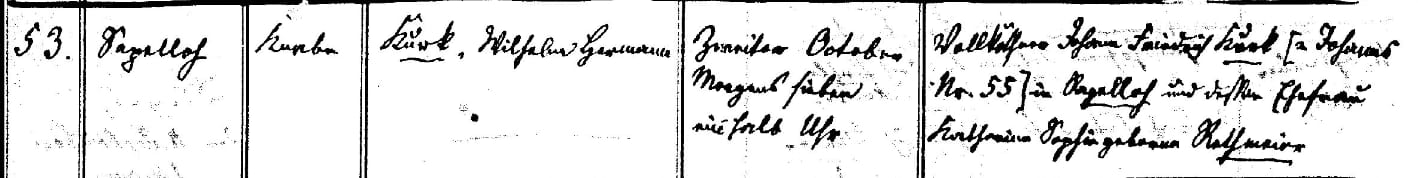

The first time I pulled up the Sapelloh church books, I sat there staring at page after page of faded ink. And then I saw it: Wilhelm’s name. Written by hand in 1859 by a pastor who probably never imagined anyone outside that village would ever see it. In that moment, genealogy stopped being abstract. My family’s past wasn’t just a story — it was right there, ink on paper, still preserved against all odds.

The experience isn’t perfect though. The pages aren’t indexed, there’s no handy search box to type in “Wilhelm” and have his records pop up. It’s still the raw books — scanned page by page. But maybe that’s the point. The records are preserved, the world can reach them, and for people searching for their family, history is accessible.

AI to the Rescue

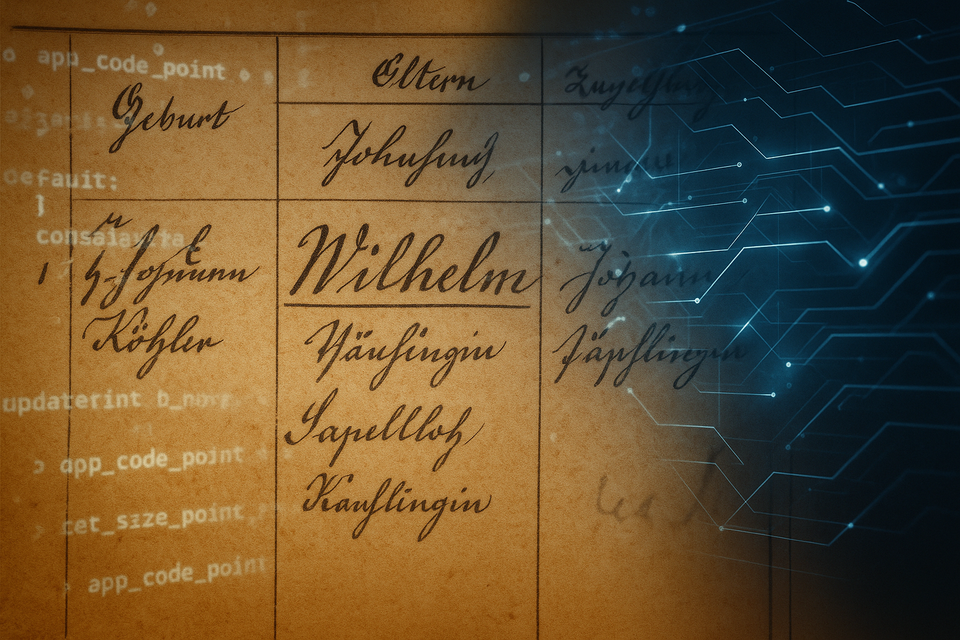

When I first opened the church books from Sapelloh, I felt like I was staring at pure noise. Faded ink, spidery handwriting, half in German, half in Latin, and all written in Kurrent. The only words I could pick out on my own were Wilhelm’s last name and Sapelloh (his village). Everything else looked like tangled scribbles.

So I started experimenting. Whenever I found a likely record, I downloaded the page, cropped it to that single row (often just single sections of the row), and asked ChatGPT to read it. It did surprisingly well. It worked especially well on the smaller sections. On a few entries, it gave me conflicting translations. When I pointed out the conflict and reminded it what it had said before, it would re-read and correct itself. I used the details I already knew, like names and rough dates, to sanity-check the results.

That’s how I found Wilhelm’s birth record. For the first time, I wasn’t just seeing his name, but the names of his parents. It listed his mother and father, what his father did for a living, and even their address.

That one detail — his father’s occupation — opened a door into the world they lived in. Wilhelm’s father, Johann, wasn’t just another farmer. The record described him as a full Köthner, a term used in 18th- and 19th-century Germany. A full Köthner was a small landholder — someone who owned a cottage with land attached, enough to farm for his family and sometimes employ others. They weren’t aristocrats, but they weren’t landless peasants either. Köthners also had standing in the village, a voice in local matters.

And the address? The house is still there. I typed it into Google Maps, zoomed in on Satellite View, and saw the old farmhouse with my own eyes. To sit in the U.S. and look at the very place where my great-great-grandfather lived and worked — it felt like AI had handed me back a piece of my family’s story that would’ve otherwise stayed locked in ink and dust.

The records also filled in family history I wouldn’t have otherwise known. Wilhelm had several brothers. The entire family, I discovered, left Germany for the U.S. — except the eldest brother.

ChatGPT helped me understand why. In 19th-century Germany, when a father retired or passed away, the eldest brother inherited everything. So the question of why the others came to Louisville was simple: no one but the eldest had anything worth staying for. The rest chased the promise of a better life across the ocean.

That led me to wonder — if the eldest brother stayed behind, does that mean I still have long-lost family in Germany? The short answer is yes, and I found a few after a year of searching. But that’s a story for another article.

Into the Maze of German Citizenship Law

As I pieced together Wilhelm’s story, another question began to nag at me: Did my family ever actually lose their German citizenship?

That question dropped me headfirst into the wild world of German nationality law — a thicket of rules, amendments, and historical quirks that even native Germans struggle to untangle. For me, it was completely foreign ground.

At first, I wasn’t sure where to start. Citizenship law stretches back centuries, with rules about when citizenship is passed down, when it’s forfeited, and how long emigrants can stay “German” after leaving. The deeper I went, the more confusing it got.

This is where ChatGPT became more than just a tool for reading old records. It became my guide through legal history. I fed it fragments of German law and asked it to explain what they meant in plain English. I asked questions like: If Wilhelm left in 1883 but returned briefly in 1889, does that reset the “ten-year abroad clock” that could strip him of citizenship? The AI walked me through the answer — yes, it did. That single return trip bought him another decade of legal breathing room.

Piece by piece, I built the timeline. Wilhelm immigrated to the U.S. in 1883, went back to Germany in 1889, and returned to the U.S. That reset his ten-year residency clock, which would otherwise have caused automatic loss of citizenship. By 1894, when his son was born, Wilhelm was still a German citizen. And — crucially — Wilhelm didn’t naturalize in the U.S. until 1920, long after his son was a legal adult. That meant his son, and every generation down to me, had retained German citizenship the whole time — so long as there were no loss events such as voluntarily serving in a foreign military without permission. Thankfully, no one did.

Of course, I didn’t just take AI’s word for it. Every step I fact-checked by comparing its summaries against the actual text of the 1913 RuStAG (Germany’s nationality law), reading commentaries, and cross-referencing with genealogy and legal forums. AI helped me map the landscape — but I made sure the ground was solid.

When it came time to file, I used ChatGPT to help draft my cover letter and supplemental notes to the BVA — the German federal office that processes citizenship cases. I wrote the backbone of the arguments myself, and AI helped me structure them the way the BVA prefers, cite the right statutes, polish the language, and translate everything into German. Using AI was about sharpening my case into something precise, grounded in law and fact.

Without AI, I might still be staring at pages of old German legal text, overwhelmed and unsure where to start. With it, I was able to build a case that showed, step by step, why my family never lost its claim — and why I was entitled to have that citizenship recognized again.

When Tech Amplifies, Not Replaces

When I look back at how AI factored into this journey, I don’t see it as a magic replacement for human effort — I see it as a tool. A tool that helped me read handwriting I couldn’t, navigate legal code I didn’t know, and stitch together a story that might have otherwise stayed buried. It empowered me to do the work myself, not outsource it.

That’s a sharp contrast to how AI is being used in so many industries today. Instead of empowering, it’s deployed to replace. Instead of amplifying human judgment, it erases it. In journalism, customer service, coding, and beyond, AI is too often wielded as a blunt instrument for cost-cutting. The result isn’t progress, it’s loss — of jobs, of trust, of quality.

Archion represents the opposite. It’s a human-led effort to preserve fragile history, using technology as an enabler. Scanning, digitizing, and putting centuries of church records online doesn’t erase the role of people — it amplifies it. It makes history accessible to anyone, anywhere, while protecting the originals for generations to come. Layer AI on top, and suddenly we can read those records, interpret them, and connect threads that might otherwise stay broken.

That’s the distinction we need to fight for. Technology isn’t inherently good or bad — it reflects how we choose to wield it. AI can flood the internet with sludge, or it can bring back a lost story from the 1800s and show you the house your ancestor once lived in.

The story of Wilhelm, and a family line nearly forgotten, came back into focus because AI and technology were used to empower — not to erase.

That’s the kind of future worth building.

-Bryan

RedBall Media runs on reader support, not ads or corporate sponsors. If you want more honest writing like this, you can help sustain it.

Member discussion